EN

He calls himself a defender of free freedom, quoting the French poet Rimbaud. Freedom that we find in the way he programmes Quintas de Leitura, a poetry cycle that is about to celebrate its 25th anniversary. He is the programme coordinator for the Porto Book Fair. He believes in Revolution. Every day, religiously, before going to bed, he reads poetry.

He was born in Matosinhos in 1953. At the age of seven, he came to live in Porto because his father, who worked for the postal service, requested a transfer to the city. His first address in Porto was on Rua do Cerco do Porto, where ‘people from the lower and middle classes’ lived. At the end of the street was the Cerco do Porto neighbourhood. ‘My best friends and even my first girlfriend were from there. The best times of my childhood, my experiences in catechism, were all spent with friends from that area,’ he says.

He studied at the Liceu Alexandre Herculano, which, in his words, ‘was wonderful’. Among his classmates, the one who stood out the most, he recalls, was Rui Reininho, two years younger than him. ‘He was a very handsome man and already had the charm he has today.’ As Gesta was not a ‘very good student’, his parents, ‘to annoy him’, sent him to Colégio João de Deus, run by priests. He didn't like it. He recalls entering the Faculty of Economics of Porto in 1972 — where he met figures who ‘made a deep impression on him’, such as Miguel Cadilhe, Daniel Bessa and Fernando Teixeira dos Santos — as ‘a deeply revolutionary period’, when he began his political activism.

Estudou no Liceu Alexandre Herculano, que, nas suas palavras, “era maravilhoso”. Dentre os colegas, aquele que mais se distinguia, recorda, era o Rui Reininho, mais novo do que ele dois anos. “Era um homem lindíssimo e tinha já o charme que tem hoje”. Como Gesta não era “muito bom aluno”, os pais, “para o chatearem”, colocaram-no no Colégio João de Deus, dirigido por padres. Não gostou. Recorda a entrada, em 1972, para a Faculdade de Economia do Porto — onde conheceu figuras que “o marcaram profundamente”, como Miguel Cadilhe, Daniel Bessa e Fernando Teixeira dos Santos — como “um período profundamente revolucionário”, altura em que iniciou a sua militância política.

It was the injustices and social inequalities he encountered since childhood that led him to study economics. ‘I had friends who went to school barefoot and whose only meal of the day was the warm bread roll with milk they were given there, and I wanted to understand how such an imbalance was possible in a European country.’ But, he says, he was “deeply naive” and quickly grew tired of university because “what we learned was not how to dismantle that.” He dropped out of university and, at around the age of 22, took on “a very tough job” at the Port of Leixões, where he was an official measurer of timber coming from the Portuguese colonies. He worked in the timber trade for more than two decades. ‘I learned as I went along, and I was good at what I did; in the final stage of my career in the forestry sector, I ended up owning my own companies, but then I got fed up.’ In 2001, the year Porto was European Capital of Culture, he launched the ‘Quintas de Leitura’, structured around the work of a poet, and then, from 2002 onwards, he continued these sessions as a programmer at the Campo Alegre Theatre.

His interest in poetry began in the 1980s. He was ‘strongly influenced by the glorious nights’ of Poetry Mondays at Pinguim, created by Joaquim Castro Caldas, who ‘was a man far ahead of his time.’ He remembers, even before that, going with Germana Tânger and his parents to see recitals ‘where people recited poetry extraordinarily well, with precision, but I found it boring.’ And so he assures that, ‘even at the age of 18 or 19, he was already thinking about how to give a fun and also much deeper dimension’ to recitals.

João Gesta © Ana Caldeira

Quintas de Leitura © João Octávio Peixoto / TMP

The phenomenon of Quintas de Leitura: the desacralisation of poetry

With monthly sessions selling out as soon as tickets go on sale, Quintas de Leitura is an unusually popular phenomenon: every month, 400 people pay to attend shows where they can hear and see poetry. The event began at Cine-estúdio, with 80 seats, moved to a room with 140 seats, and the big leap happened in 2009.

‘It's a very loyal audience and, contrary to what one might think, it's relatively conservative, but in the post-pandemic period, the audience has changed, becoming younger.’ This is also a result of online ticket sales. But there is no doubt that ‘the moment that marks the new audiences is the pandemic.’ Today, there are entire families at the screenings. ‘We see three generations, grandparents, parents and grandchildren.’

Quintas de Leitura © João Octávio Peixoto / TMP

“Desacralising poetry” and making it accessible to everyone is the main objective of this poetic cycle. “Poets are not saints. Poetry must be mixed, it must cross other fields, other disciplines.” Gesta is therefore an advocate of transdisciplinarity, of crossing various forms of artistic expression to add something to the poem.

“I remember a conversation I had with a choreographer to whom I gave a poem by Herberto Helder about Mother; she read it and said it was ‘very violent’. ‘I felt like throwing myself on the floor and breaking myself’, she said. I asked her if she wanted the challenge of interpreting it, and she [presented], at Campo Alegre, something wonderful, visceral, poetic and violent, around the figure of the mother.” — The path was clear. If poetry and music had already crossed paths, Gesta felt that dance and performance, among other things, were still missing. ‘To this day, with the help of Julieta Guimarães, from Erva Daninha, we have made countless crossovers with the new circus, and then completely crazy things.’

In these shows, where words are incendiary material, Gesta also likes to leave room for absurdity and surprise. Incidentally, he recalls the time when radio presenter Fernando Alvim took part in Quintas de Leitura and wanted to come on stage ‘in a different, disconcerting way’. "I thought and thought and said that I thought it would be funny if he arrived on stage in an ambulance; the gates outside would open, and then two stretcher bearers would bring him in, but they wouldn't treat him well; they would treat him badly and throw him off the stretcher. He really liked the idea, and that's how it went." The programmer also recalls some outdoor sessions, such as the one that took place in 2018 at Pérola Negra, a former striptease bar, now a dance club, which featured a stripper. ‘The poems were a little more risqué and the whole thing was a little more risqué, but people loved it,’ he laughs.

New voices in Portuguese poetry and music

Gesta likes to discover ‘new talents’ in poetry, which she then promotes on Thursdays: ‘A big name that is about to break through is Francisca Bartilotti,’ she says, also pointing to Francisca Camelo, Filipa Leal, Cláudia R. Sampaio, Raquel Nobre Guerra and Maria Lis as authors who deserve to be read. ‘In Portuguese poetry at the moment, and generally speaking, the female voice is much stronger than the male voice.’

The programmer also recalls the presence of Adília Lopes at one of the first sessions of Quintas de Leitura in 2002, when almost no one was reading her yet. He says that to convince her to participate, he enlisted the help of Valter Hugo Mãe, who published her at Quasi Edições. “I always tell the story of when I met her; she was presenting her book at FNAC; she was a very modestly dressed lady with a small bag, and people looked at her a little suspiciously. At one point, Adília told Valter that she had some leaflets to distribute and asked for permission to do so. She got up and started handing them out (she turned out to be the Baby Jesus of Prague!). She stopped in front of me and said: you know, I have a friend to whom God revealed himself. I was taken aback and just replied: give her my regards. And a friend I was with immediately asked me if I had sent my regards to God.”

The search for new talent also extends to music. It's a kind of scouting, like in football. ‘I often go to these bars in Lisbon and Porto to see things.’ As an example, he points to Bia Maria, but also names such as Dead Combo, Samuel Úria, B Fachada and A Garota Não, who were little known when they participated in Quintas de Leitura. ‘I remember, in the middle of the pandemic, a wonderful concert that A Garota Não gave in the auditorium of the Pavilhão Rosa Mota, with an audience of 400 people (because of social distancing, they were seated in chairs, yes, chairs, no) and almost no one knew them at the time.’

© Ana Caldeira

On the bedside table

“No matter what time I get home, I fall asleep on top of a book of poetry; I always have to read and my bedside table is full of books, so I just pick one at random.” Right now, she is reading Se Eu Quisesse, Enlouquecia (If I Wanted To, I Would Go Crazy), the biography of Herberto Helder, written by João Pedro George, and the new book by Francisca Bartilotti, yet to be published.

At the moment, “the author who most meets her standards in terms of solidity and intensity of writing” is José Carlos Barros, whom she recognises as having “a subtle sense of humour”. And, incidentally, she reads the poem “A Ditadura dos Hipermercados” (The Dictatorship of Hypermarkets): There are five continents in the world./ In Baixa da Banheira, the sixth is about to open.

He continues to discover the poetry of Cesariny and points out ‘wonderful poets who are read less and less’, such as António Ramos Rosa and Ruy Belo. ‘There are poets who have gone out of fashion, and I speak for myself when I say that Ruy Belo is rarely read at Quintas da Leitura...’

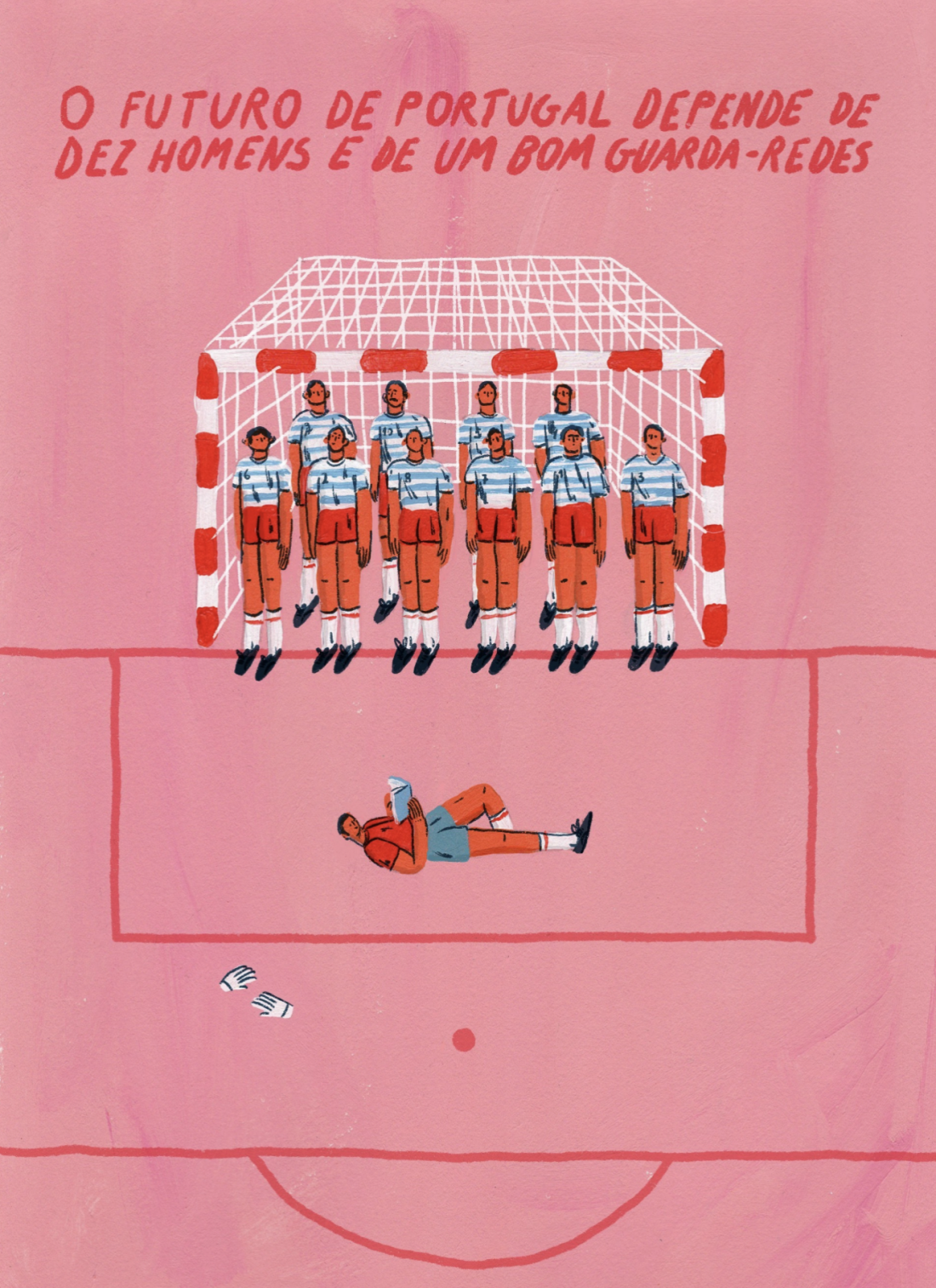

The programmer adds that the December session of Quintas de Leitura will have as its theme O Futuro de Portugal depende de dez homens e de um bom guarda-redes (The Future of Portugal Depends on Ten Men and a Good Goalkeeper), a title borrowed from a poem by Carlos Mota de Oliveira: Damas was a good goalkeeper, who knew that no one looks at a goal that doesn't concede goals. And, when he flew, he showed that there is no act more political than defending a penalty kick.

Cartaz das Quintas de Leitura © Mariana, a miserável

The addiction to Porto

‘It has always been my city.’ Gesta does not skimp on the use of possessive pronouns when referring to Porto. "When I worked in wood, I often went out, but, as Manuel António Pina said, when the plane was flying over the bridge and arriving in Porto, it was the greatest thrill. Porto, with its 10 days of continuous rain and that Sebastianist fog, is a fascinating city."

In this respect, he reads us the poem “Ponte da Arrábida” by Jorge Sousa Braga: When you come from the south, as you reach the bridge, you slow down a little so you can look at the escarpment and the river. No other city offers itself like this to those who arrive, like a bitch permanently in heat.

He continues: ‘As Sousa Braga wrote, this city is not a city, it is an addiction. [José Gomes Ferreira] wrote that Porto is the city where the word freedom is least secret. It is the city of freedom, of resistance. It has the power to lull us and bewitch us. It carries us away without us even noticing.’

We asked him to draw us an emotional map of the city. He lists some of his favourite places, even those that are now only open in his memory. ‘I just needed to live in Aniki Bobó and Meia Cave; that dimension of Ribeira has disappeared,’ he regrets, but he rejoices that Pinguim, run by Rui Spranger, continues to be ‘an important space’ for reading and disseminating poetry. “The kids bring poetry and can read freely.” Passos Manuel (“I like going there because of my friendship with Becas”), Maus Hábitos and Lusitano are other favourite places. “When I’m in a good mood, I go to Lusitano; it’s the place I find most amusing, the one I like best. And many of the drag shows I bring to Quintas de Leitura are suggestions from Mário [Carvalho]. I really enjoy Lusitano.”

Poetry and Revolution: a desire to turn the world upside down

Gesta believes in Revolution, but for now, he only sees rebellion. ‘I think this generation is a little more conservative than mine; this generation is rebellious, but it is not revolutionary,’ he says. ‘I am still waiting for a revolution that is much deeper than economic revolutions; a revolution of customs, a revolution of the body, in which touch is allowed without us being on the defensive, and in which, ultimately, the two fundamental principles that have always been upheld at the Porto Book Fair prevail: free freedom, as Rimbaud would say, and love’. Because, he laments, ‘there is a lack of love in the world’.

The cultural programmer argues that poetry is, above all, a gesture of ‘action and transformation of the world’. "I think it is through poetic writing that we have a clearer and more dizzying view of the world. Culture gives us the tools to better understand the world and act upon it; it is important to interpret it so that we can then transform it. That is what revolution is. The poet must transform the world and disrupt it, as Cesariny said," he concludes.

© Ana Caldeira

Share

FB

X

WA

LINK

Relacionados