EN

Novembro 2025

Anyone passing by number 716 on Rua de Costa Cabral would never imagine that behind the discreet façade of this bourgeois residential building lies a treasure waiting to be discovered: the incredible art collection of Fernando de Castro, who lived there. And it is no coincidence that we use the adjective ‘incredible’ — once inside, we are reminded of the words of the Portuguese writer Natália Correia: ‘I believe in the incredible.’

Paredes das escadas que dão acesso ao primeiro andar © Renato Cruz Santos

Poet, painter, caricaturist and, above all, collector, Fernando de Castro (1888–1946) transformed his home into a kind of surreal museum (without being surrealist) where gilded woodcarvings, Baroque pieces, religious art, naturalist paintings (Silva Porto is one of several artists he collected) and pieces from Caldas da Rainha abound. Everything is mixed together. There is a certain theatrical taste and an authorial touch in Fernando de Castro that seems to have carried out a work of scenography there. It is as if the house itself were an artistic installation, conceived with ostentation and creative delirium.

‘This is a sui generis house-museum, set up to the taste of its collector,’ our guide begins by telling us. ‘He collected everything he liked, whether it was art or not.’

The visit begins in the old living room and reading room, the ‘Sala Minhota’, so named because of the strong presence of this Portuguese region [Minho] in the pieces on display, through elements such as the Hearts of Viana. Right there, we realise that Fernando de Castro was not just a collector; he was also an inventor, since many of the pieces were commissioned by him — and he relied on the work of skilled carpenters. A bookcase inspired by an ox yoke or a frame with a photograph of his parents, which is actually the headboard of a bed, are just two examples among many of his inventive spirit.

Practically the entire house is covered with gilded woodcarvings in the Baroque style. This material comes from churches and convents that were closed in 1911 during the First Republic, through the Law of Separation of Church and State, and which Fernando made a point of recovering.

The dining room, filled with religious art, replicates the interior of a chapel and is separated from the rest of the house by an ornate gate that is ‘an exact replica of one found in the Church of São Francisco.’ ‘He saw it, liked it, copied it and had it built,’ says Anabela Ribeirinho, technical assistant at the Soares dos Reis National Museum. Our guide points out that ‘a characteristic of house museums is that there is always a table set in the dining room,’ but that this is not the case here because Maria da Luz, Fernando's sister, took with her the objects that ‘evidenced family life, which showed that it was a dwelling house.’

© Renato Cruz Santos

Le Malade Imaginaire, de Giuseppe Signorini © Renato Cruz Santos

We went up to the first floor and came across a ‘Golden Room’, a larger and brighter room, where the gilded woodcarving is more vibrant. It is a kind of ballroom, ‘inspired by the Palace of Versailles and the Palace of Queluz’, and differs from the other rooms in the number of mirrors that cover it and also in the absence of religious images. Of particular note is the painting Le Malade Imaginaire, by Giuseppe Signorini (late 19th century - early 20th century), which conveys a certain humour - a real figure assessing the state of health of a clerical figure.

The stairs leading to the top floor are an antechamber of wonder. The gilded woodcarving, now darker and denser, gains even more body and weight and seems to overwhelm visitors. There is an inaccessible pulpit and a collection of reliquaries without relics, the only bright spot being a colourful stained-glass window in the ceiling.

© Renato Cruz Santos

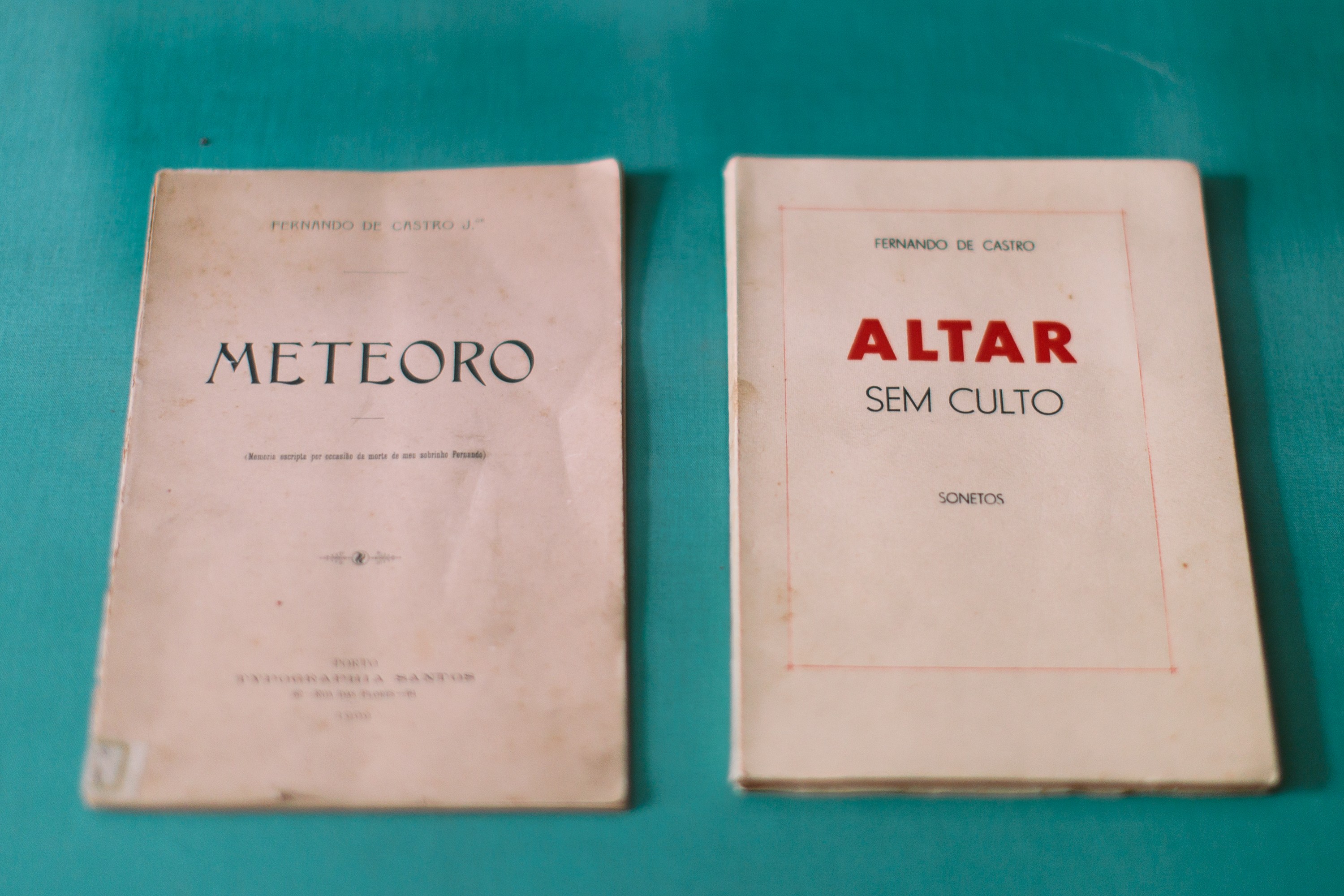

In one of the rooms, the former office, we find two of his writings displayed prominently in a showcase — Meteoro and Altar sem Culto [Altar without worship]. In total, Fernando de Castro published six works, and according to the coordinator of the house-museum, Ana Mântua, it is still possible to find ‘some lost editions’ in second-hand bookshops. Next door, in the so-called ‘Sala Azul' [Blue Room’], there are oriental objects — fans, jewellery, ceramics — which contrast with the dominant sacred imagery and reveal a boundless curiosity.

The only room where restraint prevails is the former bedroom of his sister, Maria da Luz. Here, the white walls are now covered with caricatures by Fernando, small visual satires that reveal his subtle humour and taste for puns: he liked to associate people's names with places in the country.

Between the doors that lead nowhere — or that promise passages that do not exist — and religious images and paintings that span centuries (from the 16th to the 20th century), there are other details that encapsulate Fernando de Castro's irreverent and playful spirit, such as two pieces of faience from Caldas da Rainha, hidden in the bedside table: the John Bull chamber pot and the ceramic spittoon by Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro.

Ceramic spittoon designed by Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro © Renato Cruz Santos

The scarcity of documentary sources has kept Fernando's personality shrouded in mystery, which is also reflected in the study of his art collection, built up over three decades. ‘Not much is known about his life,’ says the guide. ‘After his death, his sister, Maria da Luz, moved into the house across the street and took with her the documentation that could help uncover the origin of the collection.’

It is known that his father, who was born in Covilhã, settled in Porto after his marriage, and opened ‘a prosperous business selling glass, mirrors and wallpaper’ on Rua das Flores, becoming the national representative of the famous French Saint-Gobain glass. He was widowed early and later began a relationship with Maximina Araújo, the maid. It was from this relationship that Fernando was born in 1888 and Maria da Luz two years later. Their father recognised them as his legitimate children and, in 1893, had a house built on Rua de Costa Cabral, ‘in a prime area of the city’, where the museum stands today — a symbol of the bourgeois rise of the time.

When his father died, Fernando inherited the property and the business. And it was from 1918 onwards that he devoted himself more fervently to the collection that would immortalise him: an obsessive accumulation of works of art and objects, driven by a personal taste that defied aesthetic conventions.

In 1944, he decided to open the doors of his house to the city and show his collection — a rare, almost theatrical gesture that exposed his intimate universe, also inviting several journalists. Two years later, he died suddenly, leaving no will. It was up to his sister, Maria da Luz, to fulfil his wish to turn the house into a museum. In 1952, the building was donated by the Porto City Council to the Soares dos Reis National Museum.

Also noteworthy is Fernando de Castro's library, comprising more than three thousand volumes, but which remains inaccessible to visitors. However, its catalogue is available at the Soares dos Reis National Museum library and, upon request, the books can be consulted there. Ana Mântua adds that a master's thesis on this bibliographic collection will soon be written.

To this day, Fernando de Castro remains an enigmatic figure. Little is known about his personal life. His home is perhaps a reflection of his inner world and his most ambitious visual poem — a place where the sacred and the profane meet, that “altar without worship”.

Estátua de Fernando de Castro © Gina Macedo

Para visitar a Casa-Museu Fernando de Castro é necessário fazer uma marcação online, através do Museu Nacional Soares dos Reis, sujeita a confirmação de disponibilidade. Em visitas de grupo, o número máximo é de 10 participantes.

Share

FB

X

WA

LINK

Relacionados