EN

AGENDA PORTO: Is this album, released shortly after the 50th anniversary of the 25th of April, merely a musical tribute or is it also a political manifesto?

GISELA JOÃO: It's even more than that. When I sing, it's the only moment in life when I feel like I'm able to explain myself properly to people, how I feel about life, who I am. And actually, I'd like to see and hear myself when I'm singing, because maybe it would help me understand myself better. So I wouldn't say it's just a political statement. I'll give you an image of how I feel: you know when you're watching the news and then you turn it off and meet a friend and they say to you, ‘mate, did you see what happened...’, and it feels like your balloon is filling up and suddenly you just want to scream? The lyrics of these singer-songwriters, these melodies, helped me feel that I had somehow managed to position myself in relation to life, in relation to the world. We are all very tired of everything that is happening. I think it's impossible for people not to be exhausted, so much so that many prefer – it's not even that they prefer it, they have no choice – to live more numb in order to try to defend themselves. I understand that, too. The album came from this desire to take a stand, to feel that, in a somewhat selfish way, I also have something to say.

So, in addition to the obvious connection to Zé Mário Branco's song, this unease is linked to your personal ghosts but also to a feeling about our collective path...

Yes, of course, my concerns come from everywhere. I don't live in a bubble; I live in relation to others, to the world. And everything that happens around me makes me even more concerned all the time. I know it's a bit of a cliché to say, ‘Have you seen this? It looks like it was written today,’ but I think good poetry, good texts, good writing have this ability to live in time and make us think, ‘This is exactly how I feel’ or ‘This is exactly what I wanted to say.’ So I can only thank the people who wrote these texts, these songs, because they help me. And another thing, when I was preparing this line-up – because this was supposed to be a concert and not an album – I realised that these songs are diluted, they've mostly disappeared, you only come across them if you really go looking for them. And it's very important that this songbook is alive and well. If, for example, you're driving or walking and you hear one of these songs, that journey, which probably takes three minutes and in the middle of your day is just a trip to the supermarket, can also help you position yourself or understand how you feel, and perhaps be a starting point for you to think about the things you just consume while you're in the middle of the foam trying to swim so you don't drown. I would feel my mission accomplished if someone said to me: "look, the other day I heard you singing that song by Zeca or that song by Sérgio, and suddenly I found myself thinking about all these things that are happening here". When people have time to think, they have time to take a stand and to speak and discuss openly. Only through much discussion is it possible to get anywhere.

In the song ‘Que Força é Essa’ (What Force Is This), instead of Sérgio Godinho's original lyrics, you opted for Capicua's more recent version, which has a more feminine and, above all, more feminist angle. Was this also to make people think in the way you just described?

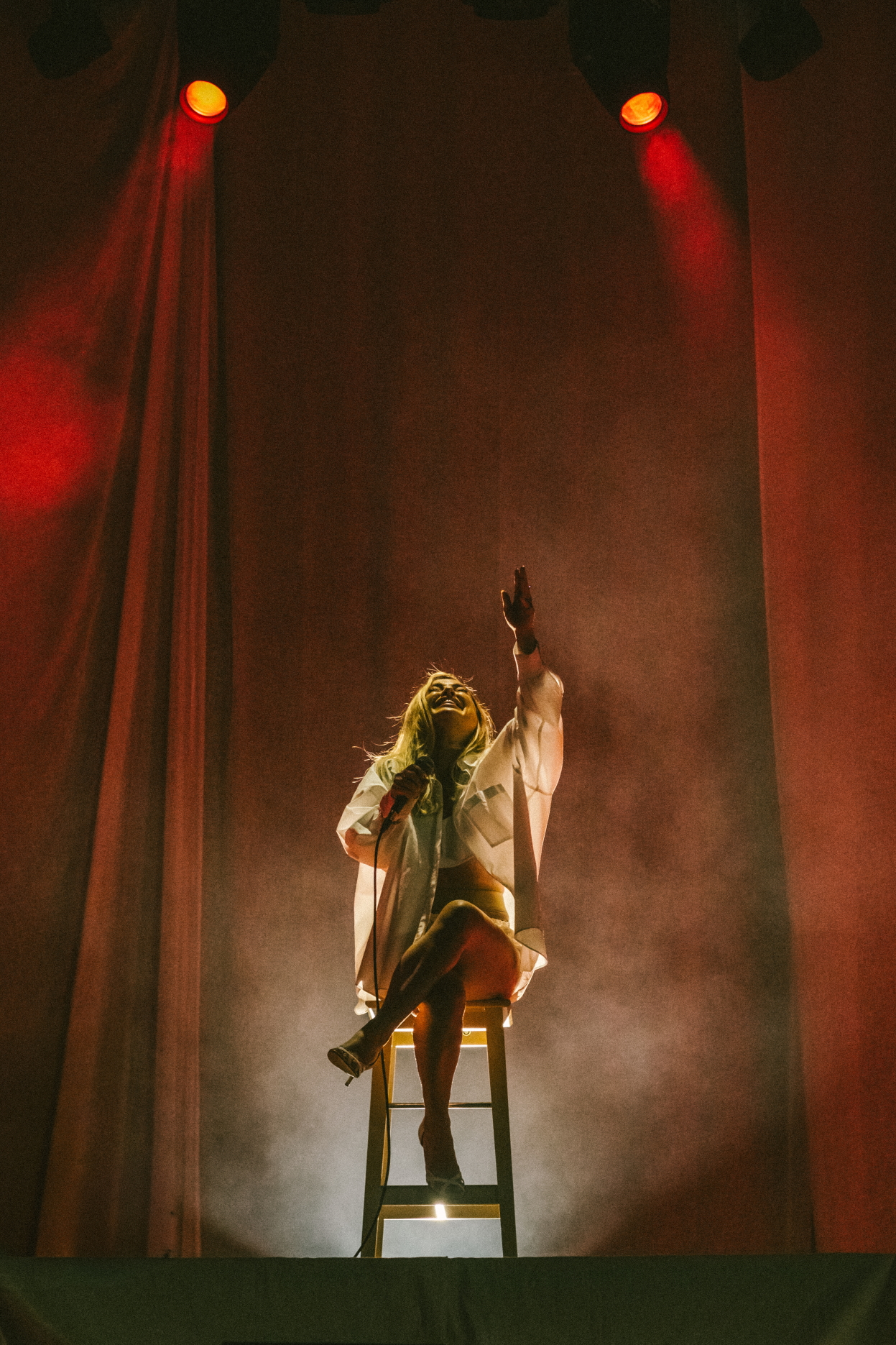

Gisela João at the Caixa Alfama festival, in September 2025 | ©Estelle Valente

It was, clearly. And to have a woman in the middle of all the songs I recorded. When Ana [Capicua] released that song the year before, on Women's Day, I was thrilled, I thought, ‘This is really cool.’ From the beginning, I wanted the album cover to be just my face with a somewhat defiant look and representing femininity, and I find it funny that it's a woman singing about freedom, since women had no freedom at all. But it wasn't enough for me to be the only one representing women, I needed more. And Ana's lyrics are incredible. I've said this many times, I'm a huge fan of Ana's, I think she writes incredibly well, it's like she's a machine where I send my thoughts, I talk and talk and talk, and then she processes it and it all comes out very well structured. There's a part in this version that fascinates me, where she writes, ‘What is this strength, my friend, that makes you carry the whole world in your belly?’ I fall in love with phrases, and this one hits me in the gut. Because, in fact, women literally carry the whole world in their bellies. Men and women come out of women's bellies.

Did you also think about your mother when making this choice? In a recent interview, you said that she worked every day and when she got home she still had to cook for seven [Gisela is the eldest of seven siblings].

I thought so, of course. But I thought about all women. Because even those who say very confidently that they don't want children have that power in their wombs. I find the image beautiful, very powerful, very dense. When faced with anyone who has those strange conversations, saying ‘no, we're not equal, women shouldn't be asking for this or that’, that sentence immediately ends any kind of discussion. Because that's how it is: where did you come from?

It's like a sentence...

Yes. And Ana had to be there too. I like the idea of continuity, of working with the people I've always worked with. I have this romantic idea that we'll be old ladies and [we'll know that] we've been doing these things, that we have a history together beyond friendship, a professional history together. I think that's beautiful.

Gisela João at the Caixa Alfama festival, in September 2025 | ©Estelle Valente

Gisela João at the Caixa Alfama festival, in September 2025 | ©Estelle Valente

You were born in the 1980s, more than 10 years after these songs were recorded. How did you connect with them?

I think I can say that these songs were very present in my generation, thanks to our parents, uncles, neighbours, television... They were present in my life from a very young age, we listened to them at home. I remember being in my uncle Queirós and my aunt Té's car, going to the river and listening to Zeca Afonso. We were kids and we sang along.

And what about fado, how did that connection come about?

Fado is something else......

because, interestingly, you come from Barcelos, a place and a generation that produced many rock bands, the Milhões de Festa festival...

Barcelos is a major creative hub for music. It's just a shame that those in charge have never realised this and have even tried to stifle all this creativity. I think it's the city in the country with the most artists per square metre. There are many artisans, lots of art, music, there has always been a lot of music. Even going back, in my city you could hear a lot of these songs [of social commentary] at concerts, on the street, in shops. It's a city that has always been very conscious. Now, fado is a completely different story. I heard Amália singing on the radio and discovered it on my own: I realised that I really liked it, it was as if that lady was singing my stories. I fell in love and went looking for more. There was a discotheque, as shops that sold cassettes and CDs were called in the old days, and I used to go there to look at things and listen to music. The owner even recorded a cassette with fados for me... I've always been a bit strange, I've never been very consensual or had a group of friends, period. I've always known a lot of people, I've always had a lot of friends with different ideas, but the first ten years of consuming fado was a very lonely path. It was a place where, for me, I could make sense. I listened to Amália sing, to Camané, and I could make sense of myself, because everything around me told me that I was a bit weird – the way I dressed, the way I behaved, the things I liked to do. So I learned to live with that lack of consensus and began to accept myself because of fado, that's the truth.

Then you came to Porto to study fashion design...

Gisela João at the Caixa Alfama festival, in September 2025 | ©Estelle Valente

Yes, but I didn't get to study. I went to Porto because I wanted to go to the old Citex, but I had to work. And when it was time to enrol, I didn't have time to study, work and sing in fado houses. I needed to earn money, because this is all very nice, but at the end of the day we need to pay the bills and put food on the table. For many years, many years indeed, I looked back on that moment in my life as a failure. Of course, I could have been working and studying and singing; there are so many people who have two or three jobs. But I've made peace with that, because not all of us have enough energy at the exact moment we need it. I couldn't do everything at once, but what I've done has been very good, it's been a lot.

How long did that phase last?

Hmm, I think I went to Porto in 2005 and stayed until 2010.

And did you sing at a place in Ribeira, or in other places too?

I started singing fado at Fado, which is still there in Largo de São João Novo – I recommend it, the food is really good – with Mr Artur, who is no longer with us. He was a great friend, a very important person, who came along at just the right time. Then I also went to sing at Malcriado, which is in Ribeira. And, as in any professional field, I got to know people, exchanged ideas, and then one musician invited me to sing at a community event, another at a party, and that was it. When you enter the job market – I think it's like that for everyone – if you're willing, opportunities will come your way. Someone once told me something I've never forgotten, because it works: ‘Luck comes your way once, the second time it's already gone.’ This is really true. Opportunities arise, we have to be able to recognise them, be available and fearless.

Was it during that search, that openness, that you realised fado would have such an impact on your life? Or was it only when you went to Lisbon?

If we talk about the emotional weight, the cathartic side that fado has always given me, it was very clear from a young age that this genre was something important in my life.

And in professional terms?

No, not at all. I thought singing would be a hobby. Just as there are people who like to play football once a week or others who like to sing in a choir. I thought I would have my profession, I had that mentality that many parents and grandparents had of ‘so what about a real job?’. The arts were something very distant, that was ingrained in me, I didn't think it was even possible. I remember that a friend, Ivo, was constantly saying that I should go to Lisbon. I laughed and said to him: ‘Are you crazy? All the famous [singers] are there, what would I do in Lisbon?’

Do you think that fado, in terms of identity, belongs only to Lisbon or is it something national?

National.

But you are one of the exceptions, because most of the leading fado singers were born or grew up in the Lisbon area...

There are fado singers who were important, even very important – and musicians too – who were from the north, and many people don't know that. Tony de Matos, Maria da Fé, Beatriz da Conceição were from Porto. And you can't talk about the history of fado without mentioning these people, for example. But they had to go to Lisbon, like me. I think fado is an almost perfect representation of the heart, the emotion and the way the Portuguese feel. I think it's there in that place, and that's why it belongs to everyone. A Portuguese person living outside Portugal feels fado in a way that other people don't. In Lisbon there were more fado houses, there were more taverns, there was more fado bubbling up all the time, but I don't think it's Lisbon's music, I really think it belongs to all Portuguese people. Now, as with many things, unfortunately, you have to go to the big city for opportunities to happen and for the path to begin.

Gisela João at the Caixa Alfama festival, in September 2025 | ©Estelle Valente

This album features pianos, distorted electric guitars, and more experimental sounds (such as brooms sweeping and buckets of water being emptied). When you compose, do you always feel connected to fado, or do you feel first and foremost like a singer and songwriter?

In this case, I am not a songwriter; in these songs, I am only doing the arrangements...

... yes, but in more general terms?

... in terms of production, I think fado is in everything I do, even in what I choose to make for dinner. I think it's much more a way of looking at life than the shawl, the Portuguese guitar or the black clothing. Fado is in the way I look at life, but it's always very important for me to avoid making what I do sound like fado just for the sake of it. I don't like things that are made to sound like something. Things have to be what they need to be, honestly, and they're interesting if they're done that way. For example, that sound of the broom [in the song Que Força é Essa] was necessary for me, because when I look at that poem, what I think about is the physical work that women do, which is so exhausting, and all the intellectual work they do. Right at the beginning – ‘I saw you working all day / cleaning the city of men’ – I imagined the number of women we see sweeping doorways, houses, offices. I thought about that image – my mother with a broom in front of me, my grandmother with a broom, me with a broom since I was little – and that sound had to be there. My starting point is always the poems, the story I'm telling, what it needs.

In January, you'll be returning to the Coliseu. Will the show revolve around the album?

Hey! It's not just any coliseum, it's the Coliseu do Porto [laughs]. I'm not from Porto, but I have a connection to Porto, it's where I became a woman, where I grew up, where I found myself. And I'm going to perform at the Coliseu do Porto because my first big concerts are always in the north, precisely to decentralise this idea that you always have to go to the capital.

Gisela João at the Caixa Alfama festival, in September 2025 | ©Estelle Valente

Then you'll be back here in June for Primavera Sound.

Yes.

How do you think fado fits into this type of festival, which is more connected to pop-rock and urban genres?

I'll repeat that maxim that I think is really true: fado is in everything I do. That doesn't mean that my music necessarily has to feature the Portuguese guitar, nor does it mean that I'm going to sing the songs that people think of as fado. I don't even know exactly what fado is! I defend myself by saying that it's much more about the way you live your life. Musically speaking, I don't know if what I'm going to do at Primavera Sound corresponds to most people's idea of a fado concert.

You're also going to Primavera Sound in Barcelona. How do you see the current moment for fado in the international context? For example, what do you think of Carminho's recent collaboration with Rosalía?

Gisela João at the Caixa Alfama festival, in September 2025 | ©Estelle Valente

I think all kinds of collaborations are very important. Personally, I don't fall in love with artists who don't experiment, who always stay in their comfort zone. I think that it is through exchange and experimentation that you can grow intellectually, musically, in everything. All kinds of experimentation are always welcome, I always applaud them.

You've performed in many countries and have several concerts scheduled abroad for 2026. Do you have any interesting stories about how you were received outside the Portuguese community?

Actually, I don't remember doing anything focused on the Portuguese community, but of course there are always Portuguese people there. And when we hug, kiss or exchange a few words, I feel like they are missing Portugal. It's as if...

...as if you belong to them...

Yes, yes, and I think that's really cool. Now, I have so many funny stories... Once, at an outdoor festival, I think it was in Zaragoza, it was very hot and it was a huge, beautiful garden. Everyone was testing the sound, and I left the venue, went for a walk around the garden and had nothing with me, no mobile phone, no ID, nothing. And when I tried to go back in, the security guard wouldn't let me in and I didn't know what to do [laughs], because I couldn't communicate with anyone...

Didn't you say you were the one who was going to perform? [laughs]

Yes, I said, ‘I'm the one who's going to sing’ [laughs], and he looked at me very seriously, very professional, and wouldn't even talk to me. I sat on a stool, waiting, until someone from my team came by and asked me what I was doing there. It all ended with laughter, because they were already looking for me.

Share

FB

X

WA

LINK

Relacionados