EN

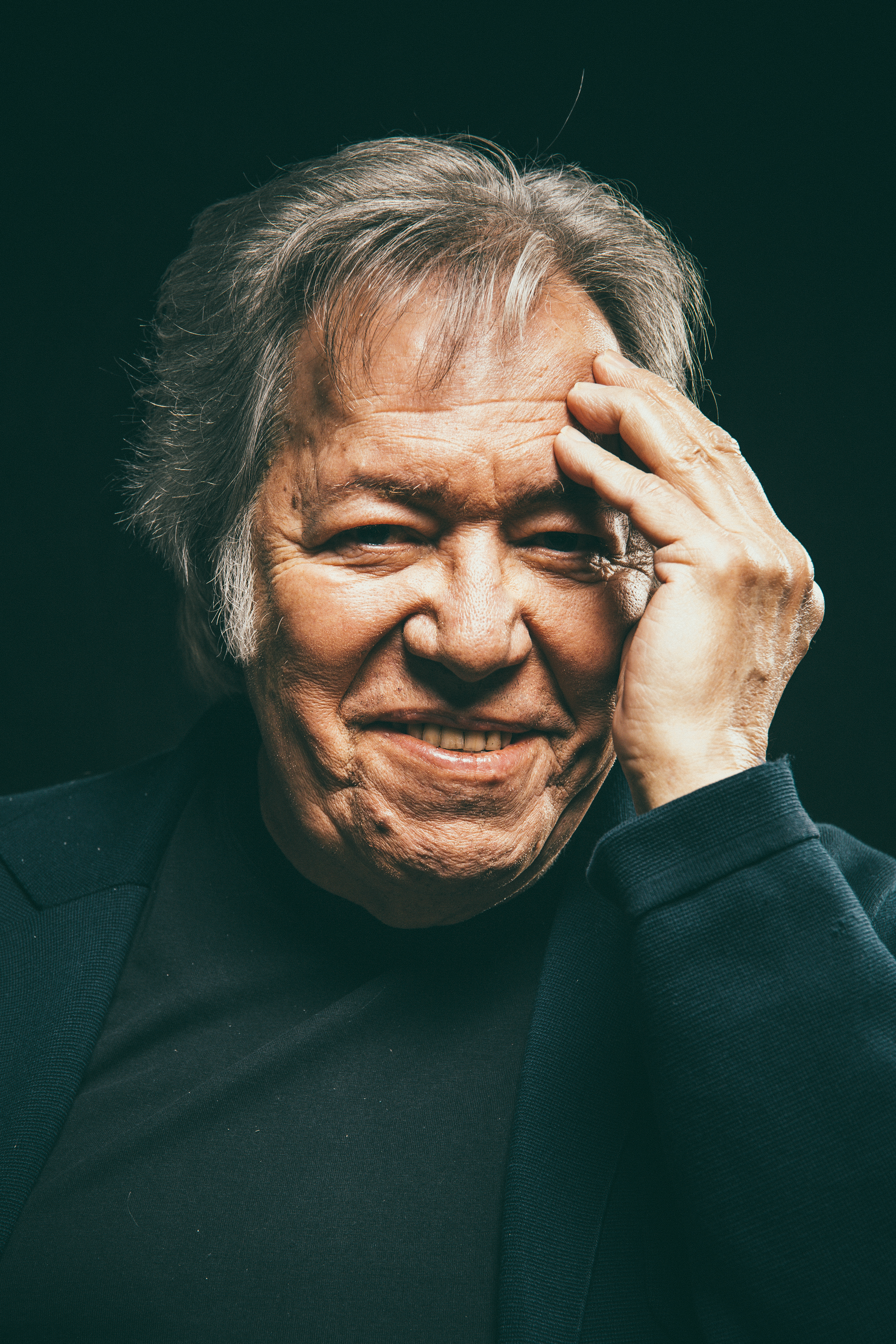

© Arlindo Camacho

In his songs live unforgettable characters like Etelvina or Casimiro, but today it's others who leave him with a twinkle in his eye. We spoke to Sérgio Godinho, the author being honoured at the next Porto Book Fair.

Agenda Porto: The theme of this year's Porto Book Fair is ‘Love and Freedom’. Are we more in need of liberating love or loving freedom?

Sérgio Godinho: We certainly need to love freedom. As for freeing love, it's not often in our hands, consciously, is it? Love is a dark force that often has no control. We tend to imprison it, but it often escapes too, in a natural way. Now you have to love freedom, but you have to love it by practising it, by making it a living object.

AP: Sérgio first studied Economics and then Psychology. Did the love of music at home - with a mother trained in piano and a musician father - help him to break free from these paths to follow an artistic path?

SG: I've had that in me, I don't know if since I was a kid. Music is a kind of second breath for me. My parents were also great writers. And my paternal grandmother had a radio programme where she spoke poetry, so I always got used to the orality of the phrase. We were members of the Teatro Experimental do Porto from the very beginning, and cinema was also a passion. I think the combination of the arts made me a richer person. I had to choose a subject and I was a bit driven to go into economics, but I had no vocation for it [laughs]. When I decided to change course and go to Switzerland, it was because I had some friends who were in Geneva and were studying psychology. But, above all, it was a good reason to become independent, to go and live my life. Not that I didn't like Porto - I've always liked Porto and my family environment - but it's clear that there were very big restrictions. At 20, I needed to have a world. In the last song I did with Zé Mário Branco, called Mariana Pais, which is on the Nação Valente album, about a young girl, I say: ‘Mariana Pais, tell me where you're going with this thirst for the world?’. I think it's a healthy thing to have.

AP: In your own words, you ‘wandered around Europe’, with little money but ‘a lot of availability’. You ended up erecting barricades and being tear-gassed in May '68. Was this freedom to be available a result of your youth or did it come more from that historical period?

SG: I think I have that in me, it's absolutely mine. In between, I did a lot of hitchhiking, I worked in the kitchen of a Dutch ship, I crossed the Atlantic... I grew up in Foz and would often go down to the sea and say: ‘one day I'm going to work on a boat’. It's different travelling by boat or working on a boat. First I travelled to the Azores, then to the Caribbean - Jamaica, Trinidad, etc. These are things that are part of the desire to fulfil stages in a journey. As for May '68, it fell on me, I didn't cause it [laughs].

Sérgio Godinho © Arlindo Camacho

AP: But you also left Portugal to avoid being called up for the Colonial War...

SG: Chronologically, let's say I left legally, because I was studying at university and I was ‘postponed’. But I knew that when I was called up I wouldn't respond, because I had nothing to do with that war, with that regime, and even at home there was already a bit of this broth. My father was completely against Salazar, although he wasn't politically active. So I ended up becoming a refractory and was only able to return to Portugal after 25 April.

AP: When you left, did you have any prospects of returning?

SG: I had no prospects, nor did I have any. I wanted to leave, I wanted to get to know people, there were no long-term prospects.

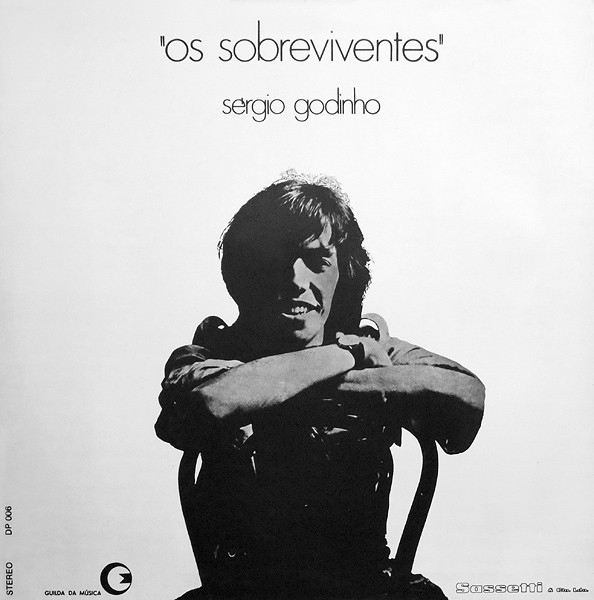

AP: Your first album, Sobreviventes, was released in '71, as were José Mário Branco's Mudam-se os Tempos, Mudam-se as Vontades and Zeca Afonso's Cantigas do Maio. Three important works of national music, all three recorded in France. How were your artistic freedom and desire for social intervention fuelled by each other? Was there a kind of love for collective creation?

SG: Yes and no. Zeca and I never made songs together - I had enormous admiration for him and I met him in Paris. He went there to record, Zé Mário and I lived there, it was different. On my first two albums and Zé Mário's first two albums there are songs we did together, perhaps the best known example being Charlatão, which has his music and my lyrics. Yes, there was an exchange of ideas. I also got on a lot with Luís Cília, who also lived in Paris, although we didn't work together. There was solidarity and friendship, because without that, it's just pretty words that are worthless.

AP: And in these times of extreme individualisation, the cult of self-love, self-help and selfies in the mirror, do you see that collective spirit being emptied?

SG: That's true, but at the same time I see a lot of people working together. Bands are appearing all the time, with fairly new people, there's theatre, there's a lot of cinema being made in Portugal, in the visual arts it's also happening in a different way. I think there are two sides to it. But, yes, there is a huge individualism. This Internet thing, social networks, etc., ends up making it difficult to focus. You're always hearing and seeing several things at the same time and you have to sort them out. Which isn't easy, really.

Capa do álbum Os Sobreviventes, de Sérgio Godinho © DR

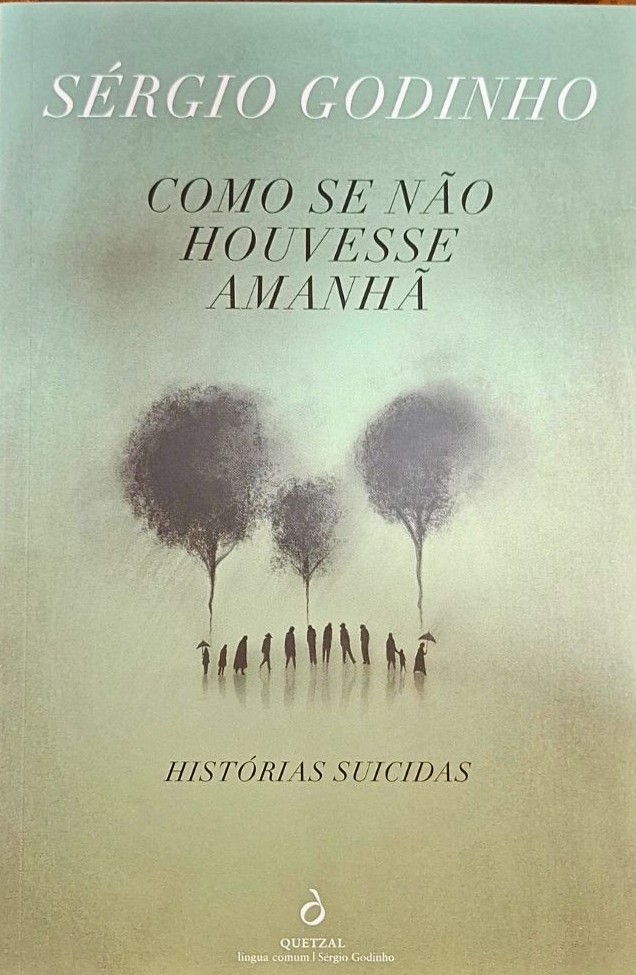

Capa do livro Como se não houvesse amanhã © DR

AP: You didn't have any problems with PIDE because you were away, but in '71 you were also imprisoned for two months by the Brazilian dictatorship. He was acquitted and released, only to return a decade later and be arrested again, with the right to electroshock. You've promised a book with more details, will that be your next project?

SG: It already is, but it's going to take a long time, because it's a work of emotional memory. It's a long-haul project, I'm starting to peel it back. In the meantime, my latest work of fiction, which consists of 15 short stories, is in the shops and will be presented at the Porto Book Fair: it's called As if there were no tomorrow and the subtitle is Suicide Stories. They're not always consummated suicides. I was interested in the human material surrounding it. It's not a down book, it's a book full of life. Personally, I have no suicidal impulse, but fiction is precisely about writing about things that aren't like us. Of course, there's autofiction, which is also a bit fashionable, but that's not what drives me. It's obvious that to talk about the prisons in Brazil I'll have to talk about myself, but in this case what interests me is looking for people I invent, who are different from me. And the more different they are, the more the fiction is built around them.

AP: There's a character in Wim Wenders who says that all stories are about Love or Death. What was the spark to write about suicide?

SG: It's still a fictional universe, I like building characters. My new endeavour in narrative fiction began with a book of short stories, then three novels and now another book of short stories. In the first book, Vidadupla, the first story is about an executioner. I thought: ‘Who could really be different from me?’. I elaborated on this and created a character. Neither I nor you, of course, would like to be executioners. That's what fascinates me about fiction, characters from a dramaturgical perspective. Shakespeare wasn't the same as King Lear, Macbeth or Hamlet.

AP: Your songs may have longer lives, you play them live, you can hear them on the radio or versioned by other musicians, but what about the books? How do you part with them when you've finished them?

SG: It's difficult when you finish. It's hard to separate yourself from those characters, from that material, because they've become yours, and in a way they also command you. This isn't a cliché. At a certain point the characters themselves are asking us: "So what now, where do I go? What do I do with this situation? What do I do with that other person I'm facing?". In a way, they're also the ones who demand of us and it's hard to leave them. The songs can, and should, be sung live, although there is always a choice. I always say that the stage is where I find the greatest raison d'être for songs. There, the song is embodied, there is an exercise in sharing, communion and also a certain confrontation, in the sense that we have to give it our all, but I think the song exists for the stage. And I have a very ambivalent relationship with studios, because... it's a hassle [laughs], it's a long, laborious process. On stage everything is at risk, but it's coming to fruition, with me and the musicians, because it's also a collective exercise.

AP: You said you read a lot at home. We know you read Eça when you were 13...

SG. ...yes, O Crime do Padre Amaro [The Crime of Father Amaro]...

AP: … and that it was also Kerouac's Pela Estrada Fora, recommended by his friend Manuel António Pina, that led him to set off for Europe. What other authors have marked your life?

SG: Wow, so many! Over time we discover others. Here in front of me I have the latest book by Julian Barnes, I like him a lot, and also Ian McEwan, two English authors of great quality. I don't know, over time I've come to like Hemingway, Flaubert, there have been so many people I've fallen in love with, as well as other Portuguese writers, of course. But I don't like making lists, it's not really my way of speaking.

AP: The lyrics of the song Liberdade [Freedom] , recorded months after the Revolution, have a refrain that is still one of the most echoed in your concerts today. Do you think that ‘Liberdade a sério’ still requires the same things?

SG: Freedom is something that's always being questioned, isn't it? When I say ‘peace, bread, housing, health, education’, and also justice and other concepts, they have to have content, otherwise they're empty words. They exist when they are more or less - and I always say more or less - fulfilled, because we live in an imperfect country. The world is imperfect too. We, for example, are a democracy, yes, but a democracy full of gaps. I wish this country didn't live with such blatant inequality, or with phenomena such as hatred, racism... I say hatred as a way of being in society, because you have to hate certain things, but not as a weapon. I think there are still a lot of injustices in this country, but there you go. You have to be aware of that path and try to do your best. It's not always easy.

AP: Zeca left early, Adriano even earlier, Zé Mário and Fausto recently... Do you feel you're the greatest living representative of that generation that set that important moment to music?

SG: I mean, I'm the only one left now, aren't I [laughs]?

AP: We didn't mean that [laughs]...

SG: I don't know... I think Vitorino is certainly someone important, and he's continuing his work. There are bands that do excellent work, Clã, with whom I've worked a lot, are an excellent band; Capitão Fausto are good; Capicua does very, very rigorous work, especially with words. Garota Não appeared with great vigour, Ana Lua Caiano, Márcia, Samuel Úria. I think they're renewing themselves. I don't really care if I'm the representative of that era, because I'm not really aware of the generation. I think I'm a bit intergenerational, I'm as old as I am - and I'll be 80 precisely at the time of the Book Fair [laughs] - and I'm active. So I don't want to categorise myself as being from an era, I don't care.

AP: That wasn't the intention, we know that since then you've had a career of great musical experimentation. You've released more than 30 albums, collaborated with dozens of rock stars, are considered a pioneer by many national rappers, played with the greats of tropicalism... who would you have liked to have worked with and couldn't, or haven't yet?

SG: I don't know. For example, Caetano sang Lisboa que Amanhece [Lisbon at Dawn] with me on the album Irmão do Meio. It was a beautiful collaboration, but we always had plans to do a song together. It was going to be on Coincidências, but it didn't happen due to various circumstances. Just like with Bernardo Sassetti. We did a song together called Em Dias Consecutivos [In Consecutive Days] he loved it, he was very enthusiastic and we agreed to continue and probably even do a whole album with his songs and my lyrics. And then that happened... he left very early too, a stupid thing. Death is often stupid, and when it's early it's even stupider. These are two cases, I could mention others.

© Arlindo Camacho

"A city without friends no longer has the same value: it's not a living city for me."

AP: After 50 years in Lisbon, how is your relationship with Porto today? We read that whenever you come, you take a bit of your accent with you.

SG: It's more the music of the phrase: ‘Hey, what's up?’ [laughs]. I've had a bit of a Porto accent, but never a heavy one. I like Lisbon a lot, but Porto is my root, because I lived there for the first 20 years of my life, very rich years. When the 25th of April happened, I was preparing my third album, which became À Queima-Roupa, and I came to Lisbon because the studios were here (now there are good studios in Porto). And another thing: I like discovering cities. I didn't really know Lisbon, I'd been there twice with my parents. Then my children were born there, my grandchildren, you end up creating a different bond.

But I love going back to Porto, precisely because I recognise and don't recognise the city. I recognise it for what it has in common and, at the same time, I don't recognise it for what it has evolved and become - in my opinion, more interesting, despite everything, with certain cultural facilities... Of course, there are also things that have got worse, for example the traffic chaos is greater with the advent of TVDEs, as in Lisbon. I think that if I had to choose three cities, they would be Porto, Lisbon and Rio de Janeiro. I have a very close relationship with Rio de Janeiro, I was there in March.

Paris, for example, where I lived for almost six years and experienced a lot, where I started making songs, is now a city that I know, I know how to walk its streets, but where I have no friends. And a city without friends no longer has the same value: it's not a living city for me.

AP: You mentioned children and grandchildren. Is a grandparent's love, free from the obligation to ensure survival, freer than a father's love?

SG: No, I think a father's love is a very strong force. I have three children and it has always been a very, very strong force. I was a very present father - and I am, but now they don't need me any more. That's not to say that I don't enjoy being a grandfather, it's just that it's more uncompromising. But the love of a father was very great.

AP: As you mentioned, you'll be 80 soon. Does that mean something special?

SG: It's a bit scary. You think, ‘Oh man, it won't be long now’ [laughs]. It's like that, whether you like it or not. I'm not as mobile, I have a serious ankle problem that makes it difficult, but my head feels fine. And this adventure of writing fiction has really revitalised me. My mind is still agile. For example, I don't read my lyrics at shows, it's all here [points to his head]. As long as that's the case, it's fine, but if I have to read them... there are people much younger than me who use teleprompters and it's not a sin.

AP: You've received many honours. Do you like the idea of having a linden tree named after you?

SG: I think it's a lovely idea. It's romantic in a way, isn't it? What's more, it will have a phrase of mine, from a song, so it will become my tree. I've already planted a few, by the way, but that one will be in my beloved Palácio Cristal, which is also from my childhood. It's something very, very familiar to me. It's curious that we call it the Crystal Palace when the Crystal Palace itself no longer exists, but it's still the Palace. For me, it has great sentimental value, yes, it's a great joy. I've had a lot of awards, last year I was awarded an Honorary Doctorate by the University of Aveiro, but having a tree that is mine and that belongs to the people, since it's in a public place, is something that pleases me very much.

Share

FB

X

WA

LINK

Relacionados